Wednesday, September 4, 2024

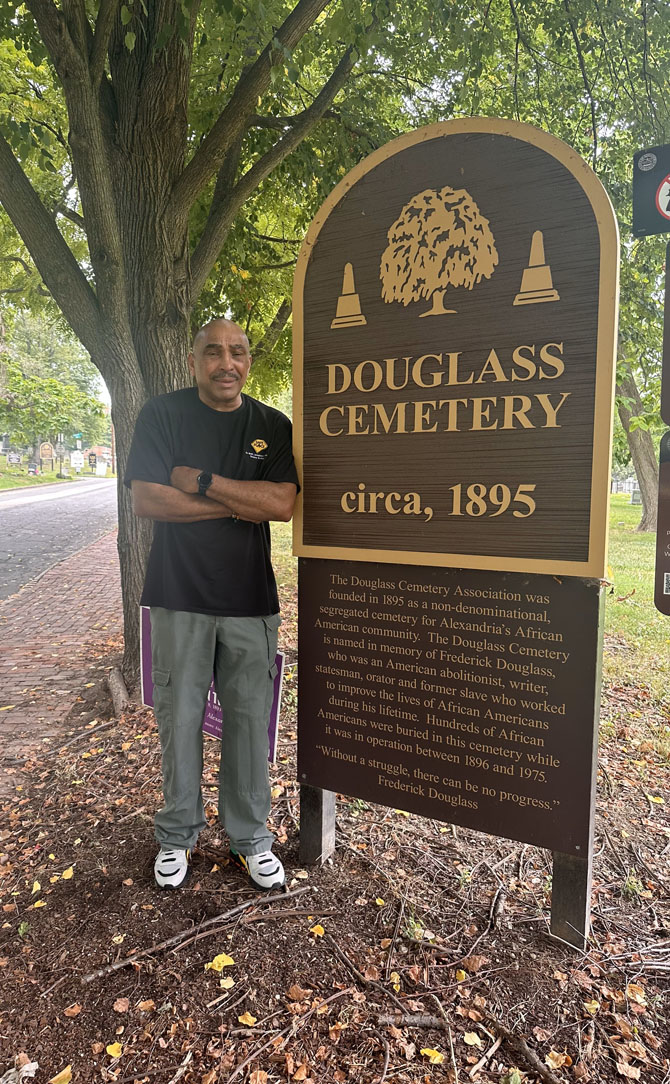

Photo by Janet Barnett/Gazette Packet

Michael Johnson stands at the entrance to the historic Douglass Cemetery on Wilkes Street. He will present an update on preservation efforts Sept. 8 at the Alexandria Black History Museum.

—Michael Johnson on the preservation of Douglass Cemetery

Michael Johnson is a life-long Alexandrian, born and raised at a time when the city was divided by race. As a kid, he used to play in a field overrun by weeds, not realizing until decades later that it was the Frederick Douglass Memorial Cemetery, a historic African American cemetery where generations of his ancestors are buried.

Now, as an adult, Johnson is focusing his time and efforts on restoring the cemetery and honoring the more than 2,000 free and enslaved African Americans buried there. The recipient of a $10,000 preservation fellowship from the African American Fellowship Program as part of the Voices Remembered initiative of Preservation Virginia, Johnson will present an update on his research Sept. 8 at the Alexandria Black History Museum.

“My family dates back to 1790 in the state of Virginia,” Johnson said. “But it wasn’t until I was well into adulthood that my mother casually mentioned that the parcel of land that I used to run through was a cemetery where my ancestors were buried. It was so overgrown no one realized it was a cemetery.”

Johnson learned earlier this year that he was one of five recipients of the fellowship.

“I am using the fellowship for more research,” Johnson said. “I want people to know how Douglass became a cemetery. I want to tell the stories of the individuals buried there. I am still locating descendants and so far have tracked down about 135 descendants around the country from as far away as California and New Mexico. But there is still a lot of work to be done.”

Located at 1421 Wilkes Street, Douglass Cemetery is facing several preservation challenges, including flooding and drainage problems, which are complicated by the presence of unmarked burials.

“Preservation of the cemetery has been a hot button item the last few years,” Johnson said. “Six years ago you would come here and see the flooding - it looked like a lake. But now that the first wave of money has come in, improvements are being made.”

Those funds are part of a $500,000 grant from the state to restore and preserve the headstones.

“Gretchen Bulova, Director of the Office of Historic Alexandria, petitioned the state for these funds,” Johnson said. “The city cuts the grass now although straightening the headstones is not a simple process. There is historical significance there and a special technique is needed to clean them. The city’s archeology department will oversee that.”

Johnson expects restoration to move forward in the next few months.

“We hope to level out the ground and work on landscaping to prevent some of the flooding,” Johnson said. “Then we will start resurrecting some of the headstones and begin the process of the cleaning.”

The Douglass Cemetery Association established Douglass Memorial Cemetery in 1895 as a segregated, nondenominational African American cemetery and named in memory of Frederick Douglass. That year, the Alexandria Gazette reported, “A force of workmen is employed in opening the walks, grading the ground and grading an entrance at the new Douglass Memorial cemetery for colored people, on the western outskirts of the city. The owners of the property [are] preparing to erect a monument in the center of the cemetery to the memory of Fred. Douglass.”

Johnson, the community outreach and safe place coordinator for the City of Alexandria’s recreation department, is also a co-founder of the Social Responsibility Group, a nonprofit organization which describes itself as “dedicated to enriching the lives of the disenfranchised.” The Social Responsibility Group is part of the efforts to restore and preserve the cemetery which oversaw burials from the late 1800s through 1975, when the last burials took place.

While the cemetery contains more than 2,000 interments, only 650 headstones are visible today.

“My theory is that some were built over but no one knows for sure,” Johnson said. “And there are 200 headstones for babies, some with names, some without. And unless a midwife recorded the date of birth, some are just marked with a date of death. Those are the stories I want people to learn.”

A father of three college graduates with eight grandchildren, Johnson has several family members buried at Douglass Cemetery dating back to his great grandfather Warner Johnson.

“Part of my work is to map out what I want Douglass to look like in the future,” Johnson said. “Douglass was supposed to have a statue of Frederick Douglass built on that site but it was never built. The Alexandria Gazette reported that white neighbors put out a false rumor that Frederick Douglass was recruiting black men to rape white women. That’s how it was back then. One of my goals for the future is to get a monument actually put there.”

Johnson will present an update on his research and preservation efforts Sept. 8 at the Alexandria Black History Museum, located at 902 Wythe Street. The presentation begins at 6 p.m. and is free and open to the public.

“When you have this much history in a community it needs to be shared,” Johnson said. “It shouldn’t take being an adult to learn about the city where you were born and raised.”